Bissau

Cupilum de Cima, Bissau, 2018.

Thirty of Bissau’s forty urban planning areas are deemed informal or spontaneous, 85% of its dwellings have no direct access to water and electricity (MOPCU 2005, Andrade 2011) and while there are few cases of ultra-dense slums common to other metropolis in the Global South (dwellings are usually well distributed in settlements, i.e. with space between them), a significant percentage of its neighbourhoods are undeniably poor urban environments.

Such state of affairs is rooted in the city’s uneven development during the colonial period, where urban plans were an integral part of a highly segregated society, instituting a complete spatial separation between the white colonialist city centre and the suburban ring (Silveira 1989). The latter was where different populations lived (ethnic Pepel, Mancanha, Mandinga or Beafada, among twenty other ethnic groups; or religious Muslim, Catholic or Animist) yet they were broadly defined as ‘native’ or ‘indigenous’ (see more, Intervention Model VII). This urban periphery did not have infrastructure, with the exception of two neighbourhoods (Santa Luzia and Bairro da Ajuda) built by the colonial administration for a minority among the urban poor. Santa Luzia was built for ‘assimilated natives’ in 1948; Ajuda to rehouse people whose homes were burnt in a large fire in 1965 – such projects were part of the late colonial urban development plans (Planos de Fomento) devised, first, to stabilize the workforce needed for the developing colonial economy and, later, to appease populations as the liberation wars went on in the rural areas (Domingos 2015). Yet while the two neighbourhoods amounted to a few hundred dwellings, the periphery was estimated to have 30,000 inhabitants at the time (Acioly 1992: 16; Milheiro 2012: 22-25).

Then, in the decade after Guinea-Bissau’s independence in 1973, persistent rural migration to the city saw it grow substantially, and the process became acute after the Structural Adjustment Program in the mid-1980s. The city reached 384,600 inhabitants in the Census 2009 and an estimated 450,000 inhabitants at present. It is not a large metropolis but, in its own small scale, has experienced a similar process to other African capitals, that of a tenfold increase in population over the past 40 years.

The majority of the areas outside the city centre lack basic infrastructure and services, and Bissauans lead a complex and often shifting everyday life in the pursue of water, electricity, education or health. Urban life in Bissau, as in other African cities, is still of a conditional, provisional and fluctuating nature (Simone 2004). One example, simply the latest, concerns the water and electricity failures in March and April 2018, caused by public utility company EAGB’s inability to buy the diesel needed to power the 19 electric plants that supply the city, which is related to the lack of support funding from the central government as well as to failed payments by households. In the meantime, the only public lighting in several parts of the city was provided by solar energy streetlights which can work off-grid put in place by a Spanish NGO – an illustration of both the country’s dependence on foreign aid and of the type of standalone alternative infrastructures devised for the urban futures of cities in the Global South. Such splintered technologies arrive at the end of long histories of infrastructure inequality, and while they undeniably ameliorate people’s lives they usually fail to structurally improve the city beyond the short term.

This said, different areas in the city have been the subject of plans and programs of intervention, following different intervention paradigms. I expand on three of them below, each with reference to a particular neighbourhood.

Cupilum de Cima

The PMBB slum upgrade program

In the early 1990s, a slum upgrade initiative called Plano de Melhoramentos dos Bairros de Bissau (Bissau Neighbourhoods Improvements Plan, PMBB) was devised for several suburban and peripheral areas of the city (Acioly 1992, UN-Habitat 2012: 50-51). The need for the plan came from a situation of rapidly deteriorating living conditions in Bissau’s bairros coupled with increasing work and food insecurity following the Structural Adjustment Program (Lourenço-Lindell 1995, 2004). There were severe problems of rubbish collection, lack of adequate sewage and poor housing as the peripheral settlements had grown substantially but did not have the infrastructure to cope. Financed by Dutch development agency SNV, the initial stage of the PMBB set out to: 1) open streets in neigbourhoods such as Cupilum de Cima, Belém, Mindará or Reno and Gambeafada (the households whose houses were in the way were re-settled in new development N’Hala), 2) build open air draining ditches, 3) provide water taps to be divided by groups of 6-to-10 houses each and 3) help residents improve their houses, namely by re-constructing them with standard techniques in cooperation with PMBB teams.

Diagram showing the cooperation steps between residents and the PMBB. Source: Acioly 1992.

One of PMBB’s choices regarded the change of dwellings’ roofs from thatched roofs to corrugated metal, as the former had been the cause of fires spreading easily through the settlements: ignited portions of straw or reed fly easily between houses and spread the fire through the settlements. The PMBB financed the wood beams (cibe) and the corrugated metal boards while the families were responsible for erecting the adobe walls, often with the technical assistance of PMBB teams, which built a construction site in each sector for residents to produce adobe blocks.

In order for the cost recovery of the funds to be achieved (a tenet strongly championed through the World Bank’s paradigm of slum upgrade, see Alexander 2012), the new houses included extra rooms the families could rent out to pay for the investment made. Indeed, the collection of these rents was directly done by the PMBB staff until all the installments of a given household were paid (Interview, Feb. 2018).

A resident shows her house in the N’Hala re-settlement area (Bairro de Melhoramentos N’Hala).

The PMBB was the last comprehensive effort to improve the housing and living conditions in many areas of Bissau. It was financed by SNV but carried out by the Bissau City Council, so effectively there was a strong public element to it, both in its design and implementation, and it structured everyday life in many neighbourhoods in a positive way during the following years. A few initiatives that illustrate this have since been abandoned, such as the system of rubbish collection by young residents (who would get a small payment for each 100 litre bag they deposited at a pickup point) and which provided a livelihood for them. The withdrawal of this modest yet hopeful initiative had to do with the inability of the City Council to continue to provide a truck and small funds to make it happen. This is a result of Guinea-Bissau’s complex politics regarding the distribution of state resources by political elites to civil society (see Chabal and Green 2016) but it is still surprising given the Bissau City Council has enough revenues coming from the lease of land to developments and even individual settlers to afford a truck (Interview, Feb. 2018).

Cupilum: from ‘indigenous’ settlement to a well located ‘middle class’ area

Cupilum was one of the first settlements the PMBB worked on. The neighbourhood is one of the zones the colonial state delimited for the settlement of ‘native’ urban poor populations and has a history going back to the early 20th century. Historically with high percentages of Muslims, accounts from local residents suggest the first mosque in the area dates to 1922 (Fieldwork notes, Feb. 2018). There are a few references to Cupilum in the Boletim Cultural da Guiné Portuguesa (the Portuguese Guinea Cultural Bulletin, the official journal of the colonial administration, from now on BCGP). One of the earliest is its appearance as ‘Pilum’ in a map from 1947, represented with dispersed dwellings (BCGP n. 7/vol. 2, p. 808). Then, it appears in a survey by Cape Verdean historian António Carreiras on the people of the suburbs (BCGP, 58/ 15, p. 286) and in an article by Fernando Costa and Luís Meira on malaria. The latter discusses housing conditions in ‘native neighbourhoods’ (bairros de nativos) because they were a source of the anopheles gambiae mosquito (BCGP, 65/ 17, p. 123). Cupilum is again referenced regarding a visit from the colonial governor in 1962 (one of his yearly visits to different popular neighbourhoods; BCGP, n. 67/vol. 17, p. 476), which was repeated in 1964 (BCGP, 73/19, p. 96).

Photograph of Cupilum in the early 1960s. Source: Boletim Cultural da Guiné Portuguesa.

Then, a panoramic view is dated to the time when asphalt streets around the area were opened. Images from this period suggest dwellings were aligned after the 1965 fire, although no clear references to this were found.

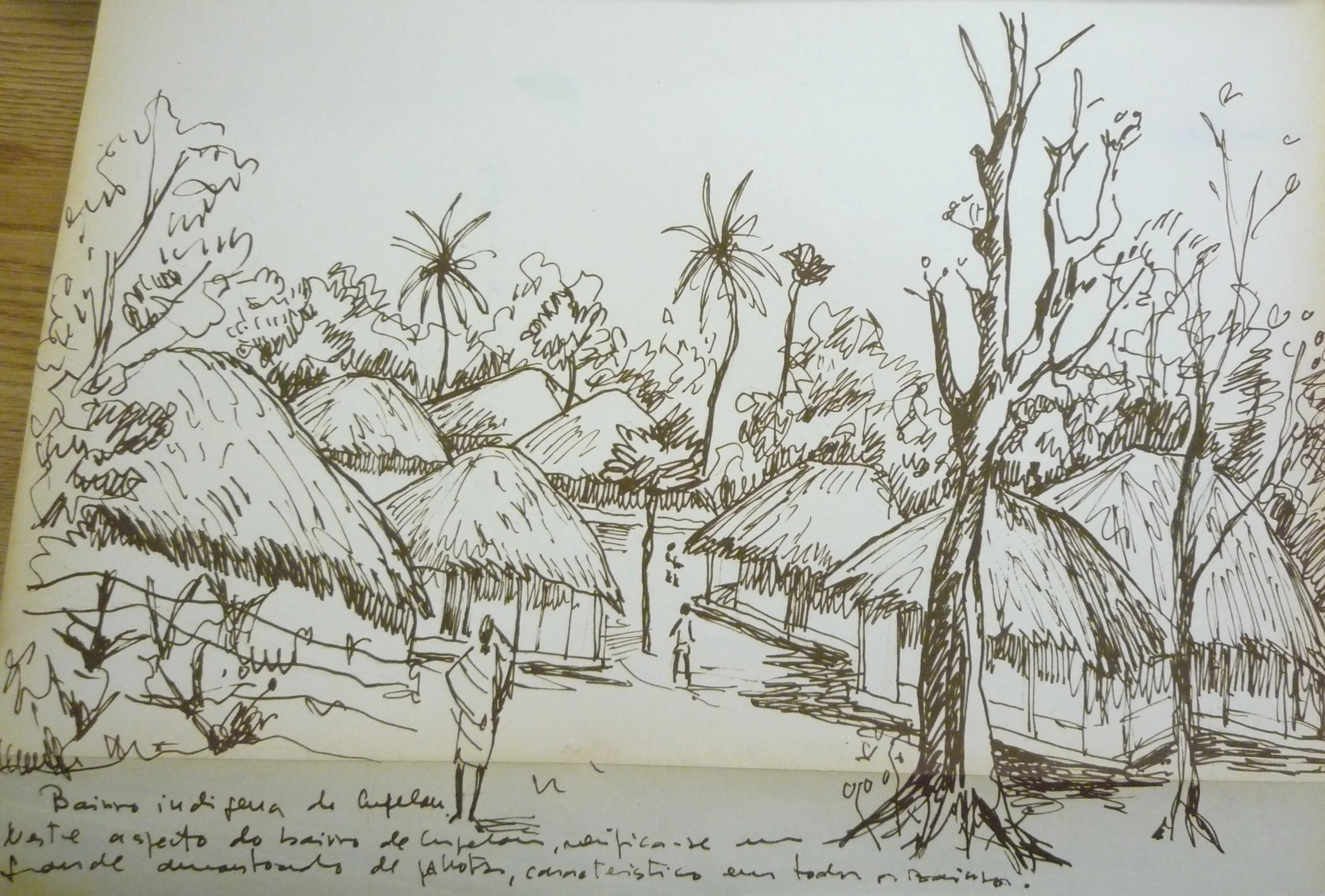

Almost a decade earlier, the colonial architect Mário Oliveira had documented Cupilum in his 1958 study of traditional housing in Bissau’s periphery, in which he noted the merits of traditional dwellings’ setting in vegetation for the tropical climate (I get back to this below).

“The indigenous neighbourhood of Cupelon”, drawing by Mário Oliveira, 1958. Source: Relatório da Viagem à Guiné, DGOPC.

Cupilum became an increasingly central area as Bissau expanded from the port area and Old Bissau to the Governor’s Palace during the late colonial period, and especially after independence. The improvements from the PMBB improved the living conditions in the settlement, and set in motion a process by which it is now almost indistinct from the adjacent urban fabric. Proximity to the centre, the improvements from the PMBB as well subsequent individual upgrades meant many dwellings in the neighbourhood were bought or rented by relatively better off households. Higher housing standards as well as individual fencing or enclosure can be found in many houses, typically those nearer the asphalted streets. At the moment a part of its population could be argued to loosely correspond to the middle class, albeit one by Guinean standards.

One of Cupilum’s main streets. During the 1998 conflict residents sheltered themselves from bombs in the subterranean sections of drainage ditches such as the one in the foreground.

Those standards do not yet include the modern infrastructure ideal of universal unlimited electricity. As with several peripheral areas in Portuguese-speaking cities such as Luanda or Maputo, the initial lack of a basic infrastructure grid during colonial times has endured well into postcolonial maturity. The pre-paid electricity meter, no matter how productive it can be in terms of navigating urban precarity and provisionality (Baptista 2016), remains the symbol of a dual infrastructure citizenship, whereby the inheritors of the ‘native settlements’ still have a different degree of access to water and electricity than the wealthier residents of the city centre.

A resident explains how his pre-paid electricity meter from EAGB works.

Belém: Re-building basic infrastructure

After the 1998 civil war that saw neighbourhoods in the city bombed by airplanes, the NGO Nadel, a spinoff from the PMBB set up by former staff from the latter, devised an initiative to help re-build houses, collective water points and a minimal sense of community in different neighbourhoods, with a special incidence in Quélélé and Belém. Below I expand on the latter.

Belém started out in the mid-20th century as a ponta, an agricultural estate leased to white Portuguese settlers. After the transfer of Guinea’s capital from Bolama to Bissau in 1941, the ponta holder left the land and it was assigned to an ethnic Mancanha chieftain (régulo), becoming a Mancanha settlement area. People lived in traditional housing in the middle of vegetation, forming a settlement not unlike those Mário de Oliveira documented in his study. Although developed with a view to gather insights from traditional architecture for modern housing, Oliveira’s study had a particular emphasis on the correspondence of architectural styles to the ethnic identity of its inhabitants.

Such correspondence was an architectural translation of the strong ethnic classification of Guinean people by the colonial state, in his case a sophisticated one, which was more generally performed with a view to divide and rule. The postcolonial period came to disavow such reified understandings, with studies showing that inter-ethnic and inter-religious alliances had always been common in Guinean society (Sarró and Barros 2016). However, during the colonial period such ethnic crystallisations had many expressions, not all as sophisticated as Oliveira’s.

Naïve drawing of a Mancanha settlement, entitled ‘Entrance of a Mancanha Morança’, by colonial anthropologist Fernando Rogado Quintino, date unknown. Source: Boletim Cultural da Guiné Portuguesa.

In essence, apart from such ‘culturalist’ interest in the traditional architectures of Guinean ethnic groups (Fula, Mandinga, Pepel, Mancanha, etc.), the neighbourhoods where colonized populations lived do not appear much in official documentation, unless when associated to epidemics.

Belém was also the birthplace of Mancanha sociétés, the community associations with an ethnic dimension that bridge traditional authority with modernity (Jao 2015). After independence, the area went through the same process of increased densification and today it is a diverse area with people from a wide variety of ethnic and religious adherences. According to the Census 2009 it has around 10,000 inhabitants.

A street with a PMBB drainage ditch in Belém, 2018.

The neighbourhood was the object of the PMBB, but it suffered significant destruction with the 1998 conflict. People fled to the countryside and many of the houses and infrastructure were destroyed. The post-war recovery project by Nadel involved the re-building of houses according to the PMBB template (funds for the house structure and the roof, self-building for the walls) and an emphasis on rebuilding collective water points.

Rebuilt water point with NGO stamps.

Here as in the PMBB, there was a need for funds to be recovered, but this time it was organized collectively, through a residents’ association set up for the effect. Future capacity was in a way delegated to the population: by structuring its activities with the need for local involvement, it was up to the residents to take advantage of that organizational obligation and transform it into a future grassroots permanent organization, as it indeed happened. The association kept records of upgrades and payments, and is today still active. Furthermore, by employing youth from the neighbourhoods to activate the program locally, it germinated future mobilization, which can be illustrated by the environmental NGO Tiniguena, which was created by people who had participated in Nadel’s project and today is one of Bissau’s cultural hubs.

Antula Bono: The S & S model

Antula Bono is an example of the paradigm of Sites & Services championed by the World Bank and UN Habitat, which is usually developed together with slum upgrade projects, as twin parts of broader frameworks for housing the urban poor after Structural Adjustment Programs (See Intervention Model VI). The neighbourhood was developed as a municipal scheme of land division and basic infrastructure provision to its 777 plots, divided into four categories to encompass different social strata in an area 4km away from Bissau’s city centre. It was part of national program Programa de Acção Social e Infra-estrutural (PASI), which aimed at tackling SAP’s worse impacts, in this case the severe housing shortages in Bissau. The scheme at Antula Bono involved a partnership between the state and UNDP (United Nations Development Program), by which the state provided the 35 hectares of land and UNDP the funding for families to buy the plots. The costs, including those of secondary and terciary improvements, were fully supported by each household through a two-year credit with 7% interest rate. Once these loans were paid, the scheme would give a second credit for families to build their houses through assisted self-building, and then they could connect them to the local infrastructure grid (Ferreira 2011, also Interview, Jan. 2018).

The main water deposits which serve the Antula Bono settlement (top), and police station, water point and drainage ditch (bottom).

Of the scheme’s four plot categories (with 150, 250, 300 and 500 square metres), the first three were dedicated for low-income households and the fourth, to be paid upfront, was open. This was an attempt to bring about a mixed-income community. Selected from 5,000 applicants, 86% of the plots allocated were ‘social plots’, and were allocated to varied segments of the population, including veterans from the liberation war. The initial phase was not without conflict with incumbent populations, as the ethnic Papel who lived there dispersedly sustained it was their land by customary rules, but the dispute was eventually settled (Interview, Jan. 2018).

The scheme built three house models (a one room house as well as a two-bedroom and a three-bedroom house) to give residents an introduction to the modular architecture envisaged by the team, in which the built structure could match the household’s income and be subject to enlargements and improvements.

A typical variation of the ‘adobe walls-corrugated metal roof’ dwelling (right, background) and a more straightforward brick structure (left). Bottom picture, dwelling of a relatively low standard.

The planning and architectural team had inspiration not only from S&S schemes directly funded by UN agencies (they visited Dakar to learn from one of the earlier and better-known cases of slum upgrade-S&S ) but also from cases in Brazilian cities. They travelled to Curitiba and Recife to learn from Chão e Teto (Land and Roof), an initiative precisely involving the lease of land and assistance for house building (Interview, Feb 2018). This is the type of travel of paradigms for slum intervention that exists in parallel with the better-known policy mobility within the English language network of large international organisations such as UN Habitat and the World Bank.

Previously, i.e. between independence and the early-1980s, cooperation had tended to be with the Soviet Union or countries from the Communist bloc. Public housing was briefly attempted with a project of mid-rise apartments, which today are dilapidated but keep the moniker of Little Moscow. In the case of the Antula Bono project, cooperation included relationships forged within Portuguese-speaking circles, which involves different affinities to those of international bureaucracy and global political blocs, in this case it was a more municipal-to-municipal relation which was obviously framed by broader plans but could still be shaped through local agency.

Construction suspended.

Accounts suggest some residents were unhappy with the small plots as Bissauans, regardless of income, are used to live with extended families and use outside space for many activities, including income-generation tasks. This would explain why many people sold their plot and house only a few years after settling in the neighbourhood (Interview, Jan. 2018). Notwithstanding, other residents, including those with higher incomes, are satisfied with living in Antula Bono (Fieldwork Notes, Feb. 2018).

Dwelling with relatively high standards and respecting the mandatory one meter free space to the plot limits.

In short, as far as Bissauans are concerned Antula Bono was not a remarkable success but neither was it a failure. In fact, it was to serve as a template for future schemes to be rolled out and tackle the continuing housing shortages in the city. However, the 1998-1999 armed conflict, followed by constant political turmoil and uncertainty, saw international organisations back away from funding further operations (Ferreira 2012: 61), and the dependence on foreign aid means the Guinean state has done very little in terms of public housing since.

References

Acioly, C. (1992). Settlement planning and assisted self-help housing: An approach to neighbourhood upgrading in a Sub-Saharan African City. Delft, Technische Universiteit Delft.

Alexander, A. (2012). ‘A disciplining method for holding standards down’: how the World Bank planned Africa's slums. Review of African Political Economy, 39(134), 590-613.

Andrade, A. (2011). (Re) Qualificação de um Bairro Periférico de uma Cidade Africana em Crescimento Urbano Acelerado. O Caso do Bairro Militar em Bissau. Unpublished MSc dissertation, Faculdade de Arquitectura, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa.

Chabal, P. and Green, T. (Eds.). (2016). Guinea-Bissau: Micro-state to'narco-state'. London, Hurst.

Domingos, N. (2015). Colonial architectures, urban planning and the representation of Portuguese imperial history’, Portuguese Journal of Social Science, 14(3), 235–255.

Ferreira, E. (2011). Problemática da habitação do ponto de vista social na Guiné-Bissau. Africana studia: revista internacional de estudos africanos, 16, 57-64.

Jao, M. (2015). Estratégias de Vivência e de Sobrevivência em Contextos de Crise: Os Mancanhas na Cidade de Bissau. Bissau, Nota de Rodapé Edições.

Lourenco-Lindell, I. (1995). The informal food economy in a peripheral urban district: the case of Bandim District, Bissau. Habitat International, 19(2), 195-208.

Lourenço-Lindell, I. (2004). Trade and the politics of informalisation in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. In Hansen, K. and Vaa, M.(Eds) Reconsidering Informality: Perspectives from Urban Africa, Nordic Africa Institute, 84-98.

Milheiro, A.V. (2012). Guiné-Bissau 2011. Porto, Circo de Ideias.

MOPCU (2005). Revisão do Plano Geral Urbanístico de Bissau. Direcção-Geral de Habitação e Urbanismo, República da Guiné-Bissau.

Sarró, R. and de Barros, M. (2016). History, mixture modernity. In Chabal, P. and Green, T. (eds.) Guinea-Bissau: Micro-State to Narco-State. London, Hurst.

Silveira, J. (1989). La spatialisation d'un rapport colonial: Bissau, 1900-1960. In Cahen, M. (ed.) Bourgs et villes en Afrique Lusophone, L'Harmattan, Paris, Françe.

Simone, A. (2004). For the city yet to come: Changing African life in four cities. Duke University Press.

UN-Habitat (2012) Streets as Tools for Urban Transformation in Slums: A Street-Led Approach to Citywide Slum Upgrading. Nairobi, UN-Habitat.