Lisbon

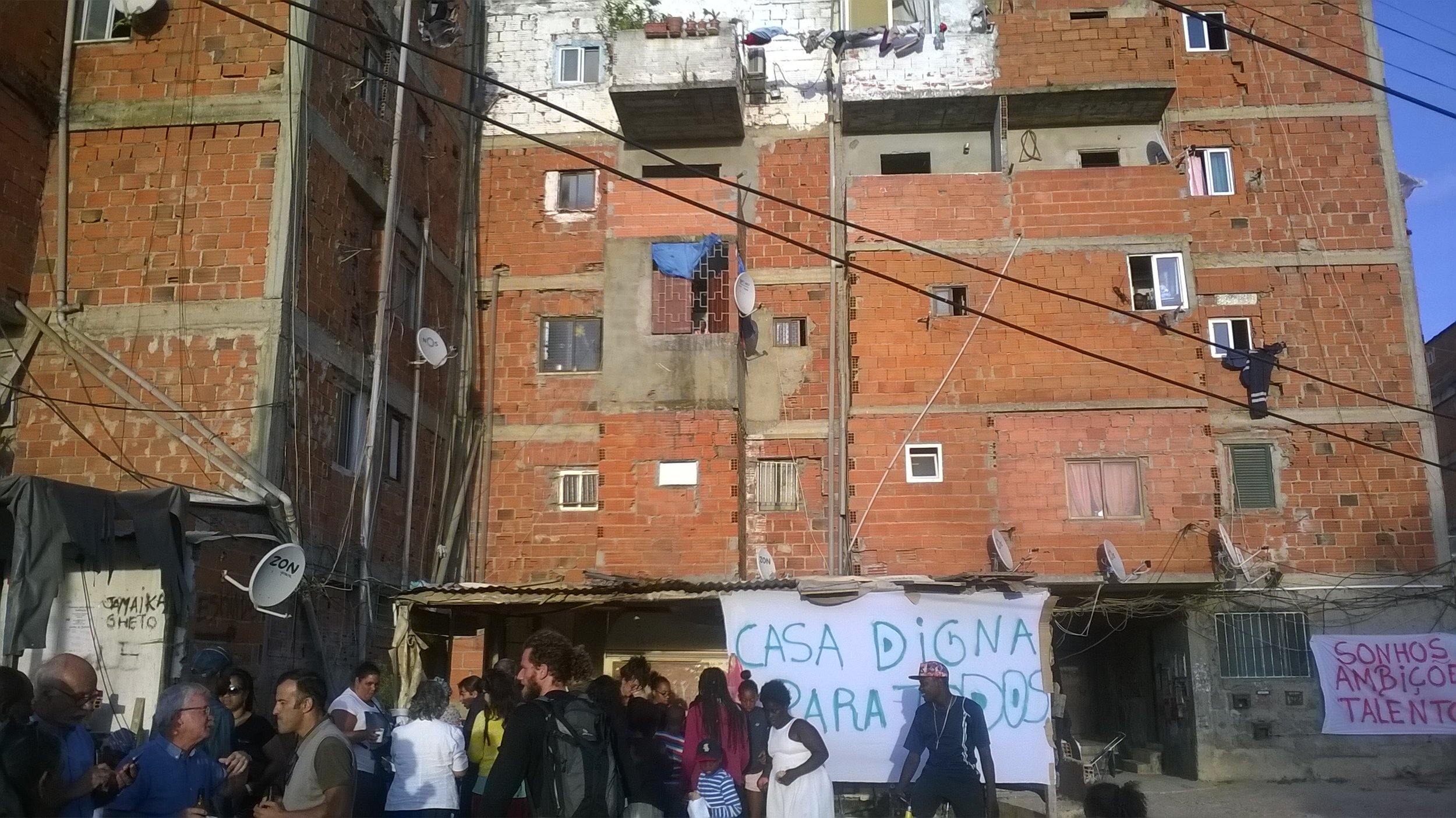

The Jamaika towers in Seixal, Lisbon Metropolitan Area.

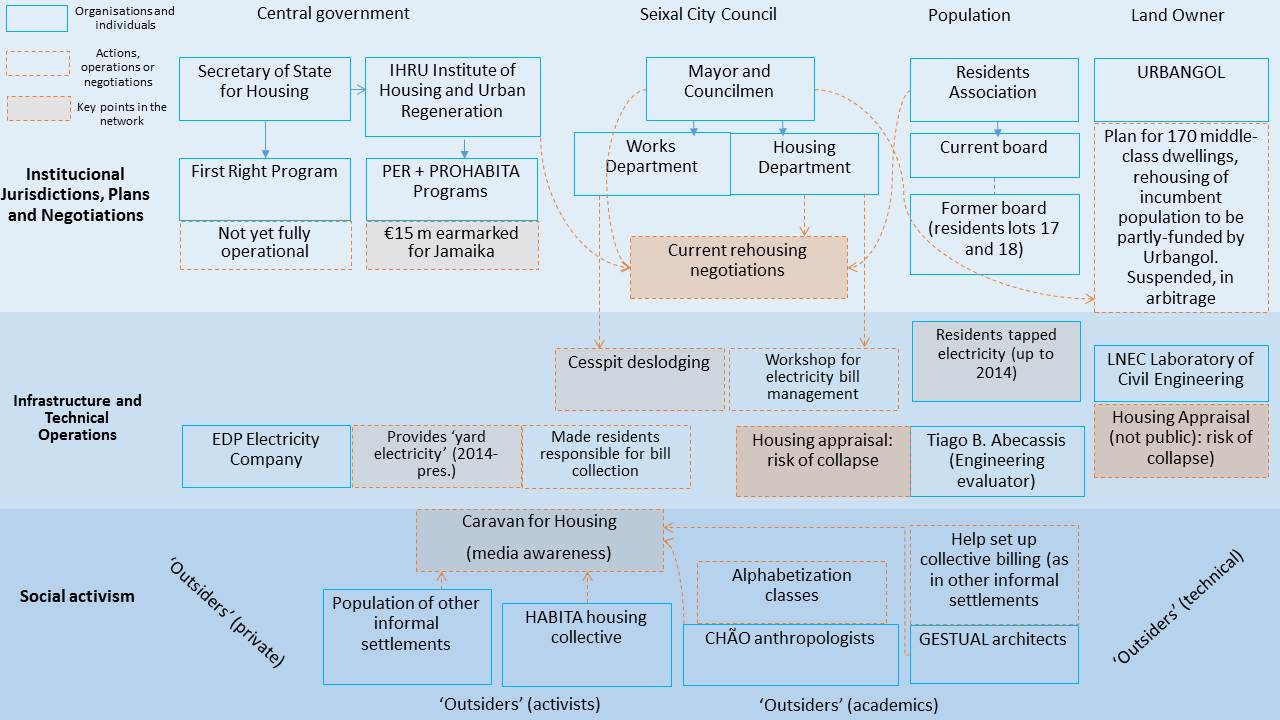

The socio-technogram of a highrise slum

Jamaika, or Vale dos Chíçaros, originates from the squatting of nine unfinished low- and high-rise residential buildings in the late 1970s, left unused after the original developer went bankrupt. The buildings were occupied by poor Portuguese migrants, immigrants from São Tomé and Príncipe and Guinea-Bissau as well as by a small contingent of Portuguese Gypsies, all in dire need of housing. The residents were first surveyed with a view to rehousing within the scope of the PER program (see Interventions I) in 1993, with several updates by the Seixal City Council in the following years. The most recent update is from 2017 and it registers 236 households, of which 97 (around 300 people) are not eligible for rehousing (Henriques 2017b).

Together with the area of Quinta do Mocho in the Loures municipality (since demolished), Jamaika constitutes a Portuguese variation on the ‘slums in the sky’ theme, such as Hong Kong’s rooftop shanties or Caracas’ Torre David. As in these cases, the self-built dimension usually associated with informal or squatter settlements appears on a previously (and expertly) built structure, the tower skeleton. It was on the latter that residents implanted their apartments by erecting walls, finishing interior spaces, laying out makeshift electricity connections, installing windows and bringing all possible portable equipment (such as heaters, fans or dehumidifiers) to improve living conditions.

The Jamaika towers are a good vantage point to explore, at the low-end of the residential highrise spectrum, what Jacobs et al (2005) – following Latour (1987) – refer to as the technogram of housing. This can be conceptualized as the diagrammatic understanding of the heterogeneous interactions between housing technologies, people and institutional arrangements and how each human or non-human agents (pipes and cables, managers and users, politicians, owners and investors) takes part respectively in ‘stabilising’ or ‘destabilising’ housing as a sociotechnical hybrid. They argue that the “ability of a highrise building to ‘hold together’ and provide a satisfactory home for its residents or to ‘fall apart’ and become unlivable – sometimes even demolished – is dependent upon the extraordinary and ordinary dramas of associations between people and technologies.” (Jacobs et al 2005: 2). The question concerns who or what are the agents and elements that hold the buildings of Jamaika together, what has made and makes them work, what type of intervention (if any) should the towers have and with what urgency should it be applied here? To answer these questions, we need to enter the network and follow its constituent elements, but at each point new questions arise and make us take some quick detours, most of which related to social and political arrangements, so at the end we arrive at something more akin to a socio-technogram.

Activist event in Jamaika, September 2017.

Structures and Risks

The socio-technical assemblage of these tower blocks, then, starts with their structure, an ordinary concrete structure common to many private tower blocks built in the 1970s, except in this case it was, in a way still is, an unfinished structure. A question this raises is whether such skeleton is able to sustain the building’s weight, windforce or unforeseen events. A tentative answer could be a yes regarding the first two, given the structure has indeed sustained the towers’ weight since it was squatted. Until very recently this had not been tested with proven scientific or engineering methods (I get back to this below), but the structure has performed its function through the passing of time. However, such assessment can be considered to be entirely controversial, in the sense that ‘historical confirmation’ of the towers not having collapsed so far does not mean they will not in the near future. As regards the third, an unforeseen event like a gas explosion which damages a pillar or load-bearing part of the structure can certainly determine the collapse of the building. Parallels can be drawn here with the explosion and collapse at Ronan Point that Jacobs (2006) studied, but hoping it is simply a similar potential risk, not an analogy to be proven correct.

Such immediate and visible risk was ignored for the past 25 years, despite the towers being part of the PER. Throughout that time, protests and complaints to the Seixal City Council (legally in charge of housing) continually fell in deaf ears. Fortunately, from 2015 onwards Jamaika became increasingly prominent to the public, on the back of several initiatives from the grassroots residents association ADSVC – Associação de Desenvolvimento Social de Vale de Chícharos, in cooperation with the housing activist platform Habita, the urban ethnography collective Chão – Oficina de Etnografia Urbana or the architect group Gestual, which aimed to draw attention to the need to rehouse Jamaika’s population with urgency.

The issue that had the most impact on political decision makers was that of the risks posed by the towers’ structures. Throughout 2016 and 2017, questions emphasizing the risk of imminent collapse kept on being posed to the Seixal City Council (SCC) and to the newly instated Secretary of State for Housing (the deputy Minister of the Environment, who has the housing brief in central government). In June 2017 radio reporter Rita Colaço, who was doing a news piece on the neighbourhood, asked senior structures engineer Tiago Braga Abecassis to make a quick assessment of two of the buildings. It was based on a naked-eye visit to two of the buildings’ exterior, staircases and one apartment in each, and while underlining this was not a standard inspection, his report is clear regarding the possibility of the two towers not resisting ‘horizontal forces caused by winds and especially by seismic activity’ (Abecassis 2017). He added other causes for concern, namely an uncertainty regarding the foundations, but was adamant that “if the structures are subject to the solicitations [stress tests] that they should, in light of the law, be prepared for, they will collapse, with tragic consequences for their occupants.” He added that even if the tests would be with forces below the legal limit the towers would still collapse (idem). In response, the Seixal City Council dispatched its own engineers. At first their inspection concluded that, on the contrary, the risk of collapse was not significant (DN 2017). The SCC further informed it would ask the National Laboratory of Civil Engineering (Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil, from now on LNEC) to carry out a definitive scientific verification to solve the controversy derived from the contradictory risk assessments. The SCC was perhaps using LNEC’s technical and scientific authority – its engineers are the highest authority in the country regarding such type of surveys – to make its view on the towers prevail, yet somewhere in the process the SCC’s assessment changed, and it started to acknowledge a significant risk regarding one of the towers (Lote 10). Such a reversal is visible in the Ministry of the Environment’s official reply to a formal inquiry by members of Parliament, where it states that “the Seixal City Council informed the Ministry that (…) based on a visit by their technical department (…) the structural fragility of the buildings is evident” (Ministério do Ambiente 2017). The letter adds that “the SCC informed the Ministry that its workers had accompanied LNEC workers on a first visit to the site” (idem), so this tells us beyond doubt that LNEC, however briefly, inspected the towers. Nevertheless, LNEC’s appraisal has not been made public, nor its existence confirmed, so it can be argued that the controversy has not been resolved yet, and it will not be until the report is published. What underpins such political oscillations from the SCC is something that remains unclear: did it prefer, at first, for the situation of stasis to persist, in order not to be financially responsible for a swift rehousing of the population?; did it change tack as it realized an appraisal of high risk of collapse would actually help to secure funding from central government?

Regardless of these and other possible doubts, the point here is that housing technical appraisal entered the domain of politics. First, it entered the arena of broad political considerations. Politicians have a logical fear of major disasters, and the eventual collapse of the towers would surely be one. In the Portuguese case, such hypothetical risk was compounded by a particular event which happened in June 2017, an uncontrolled forest fire that killed 66 people in the town of Pedrogão Grande. The firefighters’ lack of coordination was judged to be a cause for many of those deaths, this was considered a major failure by the state in protecting its citizens and major political contestation ensued. In addition, the Grenfell Tower fire in London in the same year had a significant international impact, so the type of visceral political contestation such major disasters always brings about was very present in the minds of politicians. Trying to make the Secretary of State for Housing see the urgency of acting was now a much easier task. Finally, she was just starting to draft a new housing program to substitute the PER, which was still in force but had been severely underfunded during the previous decade. The new program is called Primeiro Direito (First Right, in the sense of shelter being the most basic right) and it is designed to tackle the 26,000 households nationwide who live in ‘highly inadequate or undignified housing conditions’ – and Jamaika’s residents are among them. In short, there was now a political attention to the case as well as an administrative and financing instrument to address it.

Plans and practice

Second, the process entered the stage where it is operated by the actual workings of housing policy and practice. This second stop in the network, then, concerns the political negotiations that ensued between the local city council, the central government and residents. An absent but important agent here is the insolvent land owner, a company named Urbangol, which has developing rights on the land but also the onus of rehousing the population estimated at the time it acquired the land from the SCC. At that date, the Seixal City Council was in possession of the land because it had taken it under administrative control (posse administrativa) after the original owner had gone bankrupt. So the land, its rights and the onus of rehousing the incumbent population were passed on to Urbangol; and when the latter also became insolvent, the development plan was again halted. A situation of indeterminacy arose, one where the SCC as a municipal authority had the ultimate responsibility of rehousing the population but also one where Urbangol was the entity that had contractually taken on such onus. The logical step would have been for the SCC to open procedures to consider the deal with Urbangol as null (given the latter could not fulfill its part of the deal), and revert to the situation of posse administrativa. But it never did, perhaps in the hope that the responsibility would not fall in its arms. Such complicated state of play persisted until 2016 and 2017.

With all these things to weigh, at the end of 2017 the Secretary of State responded to the public pressure and assured that a €15 million scheme to rehouse the population between 2018 and 2022 was secured (DN 2017b). According to unconfirmed information transmitted to the residents, such funding was to come from PER parallel program PROHABITA’s remaining funds. The residents asked to be kept abreast of developments, the SCC made yet another update of eligible households and proposed a rough timeline for rehousing, but micro-controversies started immediately: two of the neighbourhood’s low-rise buildings, which were not registered as eligible for the PER, were not counted for the First Right either, and its residents started to express this was just one more example of token negotiations where everything would be decided according to the Seixal City Council with little in the way of participation.

Incidentally, some of the residents in these blocks had been part of the previous presidency of the Residents’ Association, so an atmosphere of distrust between them and the new presidency started to build up. As anxiety increased, Chão and ADVSC set up a meeting with academics who have studied the implementation problems of PER rehousing schemes (this author included), so they could share with residents what they had witnessed in other schemes and prepare them for what they would likely face in the months ahead: opaque information; discretionary decisions on eligibility; a tendency to disperse communities regardless of people wanting it or not; the preservation of the original site for private development; and other less important issues.

A meeting with residents and academics, December 2017.

Tensions related to the feud between the two factions of the Residents Association were palpable at this meeting. The most serious issue was related to building 13’s non-eligible status, which is obviously divisive. Different people warned that presenting a broken collective to institutional agents such as the Seixal City Council or the National Housing Institute would be detrimental to everyone’s case, and residents agreed, but disputes over small expenses kept appearing throughout the meeting. At a microscopic scale, it was clear that the social glue these towers and their families need to function as a community and interlocutor with state organisations was very frail.

Options and futures

The situation of indeterminacy is institutional as well as practical, in the sense of the doubts regarding what type of concrete intervention should be carried out. Four types of options could be envisaged, but given the towers have clear structural failings the first one, to rehabilitate them, can be automatically excluded. The other options would be:

a) A scheme that would see the implosion of the towers, the land cleared and the building of public housing on the site. Depending on the density to be approved it could include a part of the land to be developed for the private market and the added values act as financial support for the scheme. Such type of scheme was implemented at the Quinta do Mocho site mentioned above, with a partnership between the land owner-developer, the local government and the National Housing Institute. The problem with this option is where to rehouse people in the interim, although temporary accommodation could be arranged.

b) A second option, one that has been more often advanced, would entail the move of some residents to existing public housing in the municipality, namely at the Cucena estate, where the SCC has vacant dwellings and space on which to build. In that case, households from Lote 10 could move straight away to Cucena and the rest would do so once the new buildings would be ready. The problem with this option is that residents do not like the Cucena estate for a number of reasons, including its somewhat segregated location, the perceived poor quality of its apartments and the existence of segments of the population they do not anticipate getting along well with.

c) A third option, and the one that has been mooted more frequently, would see each household rehoused individually to dispersed locations, in a scheme not unlike the PER offshoot PER Famílias, which subsidized slum dwellers for home ownership within a specified financial ceiling. Because of this latter element, the scheme can be argued to have a characteristic of ‘in-built displacement’, yet paradoxically many people in the neighbourhood seem to prefer it, even those who will be affected by the break-up of community ties and support networks such as the informal creches women have set up among themselves to take care of their kids while they go to work. Furthermore, the First Right program has this type of logic imprinted into it, in the sense that more than increasing the number of public housing dwellings (which is diminutive, representing only 2 percent of all housing in the country) it will seek to improve offer through rent subsidies and similar instruments. For these reasons this will likely be the winning model.

Actually existing infrastructures

Until that is settled, all that residents have as their only shelter are the towers in their current condition. So I want to come back again to the ‘actually existing’ highrise slum and pay attention to it. This is where the third element that holds these tower blocks as a network of technologies and people’s agency appears.

Such element is the water and sewage infrastructure which is juxtaposed to the structure of the building skeleton. The two makeshift grids that go inside and outside the building provide water and electricity for residents in their squatted apartments, i.e. they just about ‘maintain’ the building at a minimum level of livability while rehousing arrives. Just about, and not without serious problems. The sewage tubes, for instance, are connected to a large cesspit that was installed in the building’s original basements, which the SCC intermittently desludges but still infiltrates to the soil beneath. The engineer report noted how this situation not only could be affecting the foundations’ consistency and their resistance but also that conditions of absolute insalubriousness were evident by the smells and mosquitoes coming from holes in the vertical shaft connected to the basement (Abecassis 2017). Furthermore, sometimes the cesspit overflows; it floods the ground floor; and contaminated water runs into the outside space where people usually gather and a makeshift bar functions. In May 2018, that situation happened again. Besides the hygiene concerns or the demoralizing effect such incidents have, what some residents felt more intensely was the indifference of the rest of the tower’s inhabitants to the situation. On that occasion very few neighbours were willing to help out, even as they looked down from their windows to see the current president of the Residents Association and a couple of other women “clean up all the [contaminated] water and shit” (personal communication). Just like at the meeting mentioned above, it shows a situation of social anomie, one where the atomization of desires and expectations (“to get out of this hole”) is the by-product of years of collective resistance that bore no results.

The electricity grid, or rather, the two electricity grids that have sustained the buildings are in better shape, but, once again, with relevant anomalies. The first grid is the messy grid early residents slowly built over time as they connected individual apartments to the power circuit outside the buildings, typically to street light posts. Such illegal tapping takes a degree of knowledge and expertise, as well as physical courage (accidents can happen while tapping). It was mostly made by residents who were construction workers, thus familiar with electricity connections, but it had the problem of not always being stable. The second grid was installed in 2015, after the utility company EDP – Electricidade de Portugal informed it would cease to cover the costs coming from illegal tapping. Such ‘regularisation’ of electricity provision, however, came with two caveats. First, EDP installed what is known as ‘yard electricity’ used in construction sites (electricidade de estaleiro) rather than standard lines that would go into domestic sub-divisions. This meant that costs were invariably higher than those of typical domestic electricity provision, as power was of a much higher voltage. Second, it denied individual payments by household, instead demanding that payments should be made collectively, by each tower. This meant that a type of informal representative from each building had to collect money from their neighbours and direct it to EDP. Such forced option for collective billing contributed more the atmosphere of internal conflict among residents.

A resident explains to an architect of Gestual how she was designated to check the individual electricity meters and manually count the building’s total use.

In combination with the high electricity costs (especially if we consider many families had never paid for electricity before), it fueled distrust and conflict. After a while, many residents started to refuse to pay their bills. In response, EDP threatened to cut down electricity and demanded that the Residents Association should pay the estimated €100,000 missing. This was in 2016, and to this day the process has not been solved. In April 2017 a power cut was documented by a journalist from a national newspaper (Henriques 2017a), but EDP still has the prerogative to cut electricity to Jamaika’s towers at any time it wishes. Public bodies have not been forceful enough in making clear to the company it has a duty to provide the residents with the ‘modern infrastructure ideal’ (Graham and Marvin 2002) of permanent and safe electricity, obviously with the need for payments to be made on time, but with back payments to be the object of negotiated, optimally to be mediated by the SCC.

The point this raises is that makeshift grids in informal settlements and squatted housing need complementary socio-technical operations in order to function, but other influences often come to complicate them. One is the ‘temporary curse’: because the site is to be cleared in the near future, officials from local authorities and other agents often assess it is not worth pursuing improvements, which are undoubtedly costly, and then the process drags on for years and inhabitants have to live through them with sub-standard solutions. It has been a recurrent theme in PER rehousing processes and can be summarized almost as a mantra: ‘No proper electricity because the site is temporary’; ‘no proper sewage because the site is temporary’; ‘no quality water because the site is temporary’; ‘no asphalt because…’

Alphabetization

Finally, as all these things happened, a modest activity, yet one with the potential to be a ray of light, started to be developed in the neighbourhood. Members of Chão started to provide alphabetization classes to residents who do not know how to write or read Portuguese. Most of these residents are Bissau Guineans who have a good command of their mother tongue (Balanta, Manjaco, Papel, Papel or Fula, among others) as well as of Guinean Creole, but do not know how to write in Portuguese. Every Sunday, Chão’s ‘ethnographers-cum-teachers’ provide the classes, using a phonetic methodology that abridges and speeds up alphabetization. Chão was originally interested in developing a social cartography of the neighbourhood, based on methods used by researchers who work with Brazilian indigenous peoples in the New Social Cartography of the Amazon (Nova Cartografia Social da Amazónia, see for example Almeida 2013). However, when they proposed it to Jamaika’s residents they replied that what was really needed was alphabetization, and Chão was flexible enough to change its activities. The collective now plays a very important role in the lives of those who attend classes, contributing to their empowering in a situation of uneven dealings with the state, and this also helps hold these buildings and its residents together.

***

In sum, a possible socio-technogram of Jamaika goes from the risks associated with the towers’ physical structure and their impact on political decision-making to opaque information and token political negotiations about rehousing to the actually existing low-fi technologies maintaining the buildings as minimally habitable places for residents to the social technologies used by activists, NGOs and academics trying to support the community and their future-oriented collective and individual improvement. It can look like this:

A possible socio-technogram of the Jamaika neighbourhood.

The diagram reveals a case of some complexity and also shows the use and/or adaptation of different types of rationalities and knowledge forms across one network. They include the housing inspections, the administrative census-like register of households that is the base for the negotiations, policy documents from central and local government, newspaper articles documenting life in the neighbourhood, social cartographies or alphabetization methods, each pertaining to the different operations which – more or less tangentially, more or less fundamentally – have contributed to sustain this highrise slum over time.

* Written and posted in December 2018. On the week of Dec 17 the first 64 households from Lot 10 started to be rehoused in dispersed locations. For the residents, this was good news at last.

References

Abecassis, T. (2017). Testemunho da observação de dois edifícios no dia 15 de Junho de 2017. [Brief report on a naked eye assessment of two buildings in Vale de Chícharos, June 2017.]

Almeida, A. (2013). Nova Cartografia Social: territorialidades específicas e politização da consciência das fronteiras. In Almeida, A. and Farias Junior, E. (eds.) Povos e comunidades tradicionais: nova cartografia social. Manaus: UEA, 11-36.

Chão – Oficina de Etnografia Urbana (2018). Em Busca do Colectivo: Diálogos para uma Cartografia Social. In Carmo, A., Ascensão, E. and Estevens, A. (eds.) A Cidade em Reconstrução. Leituras Críticas 2008-2018. Lisboa, Outro Modo, pp. 120-126.

Cairns, S., and Jacobs, J. M. (2014). Buildings must die: A perverse view of architecture. Cambridge, MA, MIT Press.

DN (2017a). Câmara do Seixal diz que não há risco de colapso iminente em prédios de Vale de Chícharos, in Diário de Notícias, 26/10/2017.

DN (2017b). Governo e Câmara do Seixal assinam protocolo para realojamento das famílias que vivem em Vale de Chícharos, in Diário de Notícias, 21/12/2017.

Graham, S., and Marvin, S. (2002). Splintering urbanism: networked infrastructures, technological mobilities and the urban condition. Routledge.

Henriques, J. G. (2017a). No bairro da Jamaika sobem-se escadas às apalpadelas, in Público, 7/4/2017.

Henriques, J. G. (2017b). Famílias do bairro da Jamaika vão ser realojadas, diz Ministério do Ambiente, in Público, 21/12/2017.

Jacobs, J.M., Strebel, I. and Cairns, S. (2005). Highrise Housing as a Building Event. Paper presented at the ESRC seminar ‘Housing Research and Science and Technology Studies’, Department of Geography, University of Durham, 11 October.

Latour, B. (1987). Science in action: how to follow scientists and engineers through society. Milton Keynes, Open University Press.

Requerimento 4/XIII/3ª. – AL (2017). Informação técnica sobre avaliação a edifícios de Vale de Chícharos. Pedido do Grupo Parlamentar do Partido Socialista, Assembleia da República.

Cova da Moura: Assessing informal built environments

Granting slum dwellers their right to the city through the full rehabilitation of the built environment, rather than through simple slum upgrade (see Interventions V) has been experimented in different places and times, to varying degrees of success. In the Portuguese-speaking urban landscape the option has been pursued from the renovation of the Brás do Pina favela in Rio in the 1960s to some of SAAL’s projects in the 1970s to several Favela Bairro projects in Rio in the 1990s and 2000s. Within such type of processes, assessing the actual conditions of shanties or other precarious housing structures to know if they are upgradeable is the first key moment. Below I draw on an experimental program for the rehabilitation of the Cova da Moura informal settlement in Lisbon in the mid-2000s to point out some distinctive elements of assessing informal built environments and how they interrelate with more structural issues to achieve success.

The intervention to be made in Cova da Moura, under regeneration scheme Iniciativa Bairros Críticos (Critical Neighbourhoods Initiative, from now on IBC), was partly inspired by Brazil’s Favela Bairro programme and partly situated within the ‘urban regeneration’ paradigm, only applied to a slum neighbourhood. It was an ‘experimental’ project in the sense it would use the known formula of urban regeneration (usually associated with historical centres after periods of disinvestment) in a new setting, an informal settlement. Ultimately the objective of rehabilitating the neighbourhood was not completed because the IBC program was suspended due to lack of funding, but the housing appraisal was developed and finalized by experts from the National Laboratory of Civil Engineering (Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil, from now on LNEC), so it is still a valuable element to analyse the key moment for such type of slum interventions.

The project at Cova da Moura responded to the community’s demand to ‘stay’ in Cova da Moura, that is, for their wish that rehabilitation would take place in situ, thus granting the population its right to stay put and not be displaced. This was linked to the idea of the recognition by the state of the culture and knowledge of the population who had built the neighbourhood with informal techniques and collective effort over the previous 40 years. It was a sophisticated way of acknowledging that there existed a proxy morphological and architectural identity in the neighbourhood’s urban layout and the dwellings’ architectural configurations, one that needed to be preserved. What is commonplace in the regeneration schemes of historic centers—upgrading urban and habitability conditions while maintaining what architectural historians refer to as the genius loci—was here to be applied to an informal settlement with sub-standard dwellings.

Different houses in Cova da Moura, with differing levels of architectural signification

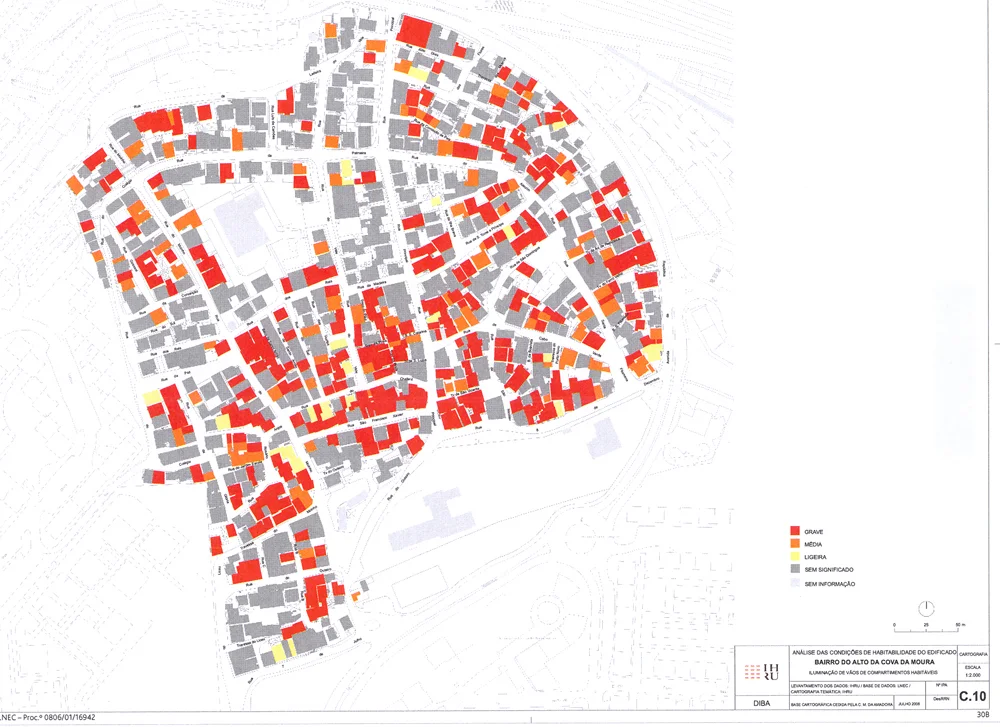

Among the scheme’s most important rules was that the houses would have to comply to standards set in dedicated regulation for the reconversion of Urban Areas of Illegal Genesis (Áreas Urbanas de Génese Ilegal; LNEC 2008: 1), a more flexible approach to housing ‘minimum standards’ but one that still assures the ‘acceptable living conditions’ enshrined as a universal right in the Portuguese Constitution. The crucial first step for this was an evaluation of the habitability conditions of each house and it was at this point the project came up against the specific technoscientific problem of how to evaluate the informal city (i.e. the non-standard city) so as to be able to bring it into the realm of the measurable, and then move to upgrade it.

Analysing informal built environments

The question was whether these dwellings could actually be rehabilitated. It asked whether the dwellings were really structurally sound and could be upgraded, for instance with pinpoint interventions at gas joints, water or sewage connections, lighting and so on; with small architectural acupuncture such as opening windows in closed facades, thus improving light and air conditions inside the dwellings; or with the demolition of adjoining houses that might immediately improve the habitability of several others. Establishing the veracity of these ‘uncertain facts’ (Callon et al. 2011) was to be answered by an independent assessment of the built environment, to be carried out by the LNEC. Housing and engineering ‘official science’ had been summoned to arbitrate this urban uncertainty.

Architects and engineers visit houses

Because of time constraints, instead of a thorough structural analysis with ultra-sounds and other robust methods, the LNEC devised a methodology of visual assessment of all the 1,617 surveyed dwellings units in the neighbourhood, based on a 20-minute visit of each one. These visits focused on the individual dwelling’s rehabilitation needs as well as on its relation to the adjoining dwellings. Such individual characteristics came both from the ‘naked-eye’ observations by the engineers and architects inside the houses and from a list of recurrent anomalies they had to check and tick the corresponding boxes in the individual file (see in detail, Ascensão 2013: 166-173).

These elements were then input into an individual database file and an algorithm rendered them into overall scores that suggested the need for light, average or comprehensive rehabilitation the dwelling required per se and in relation to others. Finally, this was graphically represented in different maps of the neighbourhood, one for each of the main characteristics to be assessed (e.g. ‘walls/bays without fire resistance’; ‘air and light in inhabited spaces’; etc.).

Map C10, air and light in dwellings. Source: LNEC 2008.

What does a computer algorithm generate?

The computer assembles the dwellings and gives them representation in a new collective, which is the neighbourhood in map form. These maps, then, become the assembly of all dwellings—with their families, dramas, problems and joys related in each case to unique, non-standard, material houses—into one coherent whole. The machine enabled making uniform what was utterly non-uniform to begin with, in a case of “distributed intelligence” (Callon et al. 2011, 57) between human observation and the aptitude of the instruments used for the elaboration of knowledge.

Essentially, the representation of people—that is, of each family—was made through the characteristics of their dwellings in a diagram rather than through any type of human-to-human dialogue. The entities that were represented were the dwellings, and the program’s later configurations would respond only to those. Such a situation belongs to the almost imperceptible shifts in the nature of social operations in late modernity whereby the agency of ‘things’ is increasingly enmeshed with, and sometimes substitutes, the agency of ‘people’ in policy and implementation; but, it is also an example of Callon et al.’s (2011, 106) cycles of translation and delegation in scientific activity, from reality to research collective and back to reality. However, in practical terms such type of mediated representation made clear that the ultimate objective it was designed for—the rehabilitation of the dwellings and of the neighbourhood in general—was entangled with a paradox hard to undo.

The evaluation results exposed a very fragile situation regarding many buildings, and the maps tellingly show that to grant most families a material amelioration of their dwellings, some of the more dense clusters of houses had to be broken up, with those in worst conditions demolished to make space for improvements. As such, a part of the population had to be displaced (Ascensão 2013: 174-175). This was the closest to certain and certified knowledge the experts had reached. The research collective had analysed the dwellings as proxy indicators of social reality and in getting back to the latter (the neighbourhood’s residents) it essentially informed them that a possible solution would rationally have to involve the neighbourhood’s re-configuration in terms of urban fabric, and thus also in terms of social composition. As a micro-political problem, it could have been solved by managing to get those who wanted out of the neighbourhood (into new-built apartments in the vicinities or, should they opt to, other places) as quickly as possible in order to free space for the rehabilitation of those who preferred to remain. Indeed, this was envisioned as a possible course of action by the project team (Interview, 2008).

But instead, it was solved by the other way of solving paradoxes, which is to bury them under a new, big fact. Such a new, big fact came from the outcome of the international competition to select the architectural and engineering team responsible for the detailed design and building of the new neighbourhood.

There were two main entrants. The first one planned to implement the rehabilitation approach but with a more robust consultation than previously managed, including a survey of all the households, ‘visioning workshops’ and walking interviews with selected residents (Raposo and Malheiros 2010). The second entrant proposed a more directive clearance and medium-rise solution, i.e. it proposed to avoid all the complications of consultation or participation at the micro-level and implement an abstract plan from scratch (Cunha 2010). Each proposal was clearly located within a different branch in the broad genealogy of intervention in informal settlements. The winner was the latter, which meant the dismissal of rehabilitation and reversion into a new-built solution, with clearance of all the existing dwellings.

Within such a solution, there was now a clear loss of ‘representation’ for the dwellings, and indirectly this also meant a loss of representation for their families, memories and expertise that the original solution was devised to respect. In the original plan, the computer software introduced a type of technical rationality that tends to override political considerations – algorithms produce values independently of judgement. However, by creating a representation for the dwellings, a supposedly ‘apolitical’ technological procedure de facto guaranteed a techno-political representation for the families, in which the dwelling and the family-household were entangled in one single entity. This loop was particularly constructive because it seemed to be able to prevent a scheme entirely imposed from the top. By contrast, in the winning proposal the diagnosis work and the technological mediation described above was to be wasted and a straightforward top-down solution implemented. Furthermore, the bigger risk for families was that this loss of representation could mean that they would not get to stay in the new buildings but rather be displaced to other sites, further away, as was common in the previous PER program.

What can be argued about this course of events is that after the delegation to a research collective and the reduction of social reality into measurable parameters, the final moment consisting of the extension of the research findings back to reality encountered a problem that came from beyond the planned procedures of the established models of intervention yet proved to be stronger and superseded them. The architectural competition re-configured the original issue at stake, which the experts had been summoned to arbitrate—whether rehabilitation was possible, and what would it entail for each individual dwelling and household—and was able to revert it into a broader binary decision on how to intervene on the site (either rehabilitate or clear and re-build). It thus re-opened the door for an option that was not there at the beginning of the process, indeed the one option that the process had been initiated to avoid. The re-emergence of the possibility of clearance and displacement, inexistent at the start of the process, was particularly advantageous for the land owners, who wished to develop the site for middle class residential development rather than for the low income groups who inhabited it. To achieve that, they enrolled a different set of rationality forms (legal and judicial rationalities, particularly those pertaining to property law within a market society) to defend their case, and did so successfully.

In short, the technical assessment of informal buildings (a complex reduction of technical parameters into a legible format) prepared the architectural competition, but the latter redefined the issue at stake and enabled the re-emergence of the option the whole process was meant to avoid, clearance.

References

Ascensão, E. (2013). Following engineers architects through slums: the technoscience of slum intervention in the Portuguese-speaking landscape. Análise Social, 48(206), 154-180.

Callon, M., Lascoumes, P. and Barthe, Y. (2009). Acting in an uncertain world: an essay on technical democracy. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cunha, V. (2010). Concurso Público Internacional Para a Aquisição de Serviços de Elaboração do Plano de Pormenor da Cova da Moura: Proposta. Lisboa: Vasco da Cunha Estudos e Projectos.

LNEC (2008) Análise das Condições de Habitabilidade do Edificado no Bairro do Alto da Cova da Moura. LNEC Report 366/2008. Lisboa: LNEC.

Raposo, I. and Malheiros, J. (2010) Concurso Público Internacional Para a Aquisição de Serviços de Elaboração do Plano de Pormenor da Cova da Moura: Programa de Trabalhos e Cronograma. Lisboa: Faculdade de Arquitectura e Instituto de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território.

A section of Quinta da Serra. C. 1990. Photograph by Irmãzinhas de Jesus Sisterhood.

Quinta da Serra: templates for building and improving an informal dwelling

The Quinta da Serra informal settlement no longer exists. It was one of the approximately nine hundred informal settlements surveyed in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area in 1993 as a part of the PER rehousing program (see Interventions I). The neighbourhood went through a process of individual demolition and rehousing of families which lasted over five years, from 2006 to 2011, and since then it has been an expectant site, planned to be replaced by upper-middle class residential buildings. Drawing on previous research on the site (Ascensão 2011, 2015), below I look at the agency of urban poor populations in building their homes, providing glimpses of the informal knowledges and low-fi technologies used by people to build their illegal/informal parts of the city.

Adjustable architecture

The first one concerns the idea of a match between the history and conditions of settlement and what is materially built. It could be termed as ‘adjustable architecture’, in the sense of homes which started out as truly makeshift shacks being reconfigured and adjusted over time – through the adding of more spaces or the use of better materials as residents had a greater income and their personal lives changed – to become dwellings with better conditions. The self-build and upgrade element tends to play out over time and is particularly leveraged by tenure security, but even when that is not the case (as in Quinta da Serra), dwelling evolution is often considered from the start.

The use of different roofing materials in different periods: fibre cement boards (foreground) and concrete slab (back, beneath four red bricks).

One illustration of this process comes from one immigrant resident who built his dwelling over his first year in Quinta da Serra in 1990, even if he was not able to build all the rooms needed straight away. But when his wife and children joined from Cape Verde some years later, he “completed it” as he had always envisaged. The succession of ‘initial individual migration’ + ‘increasing income and savings’ +‘family reunion’ + ‘house extension’ was materially noticeable in the roofing of two distinct parts of the house: a part with concrete slab roofing installed for the ‘house extension’, which was quite different and provided better liveability conditions than the initial part with fiber cement roofing and woodsheet false ceilings. See in detail, Ascensão 2011: 189-233.

Above, room with concrete slab roofing. Below, room with fibre cement board plus cardboard false ceiling.

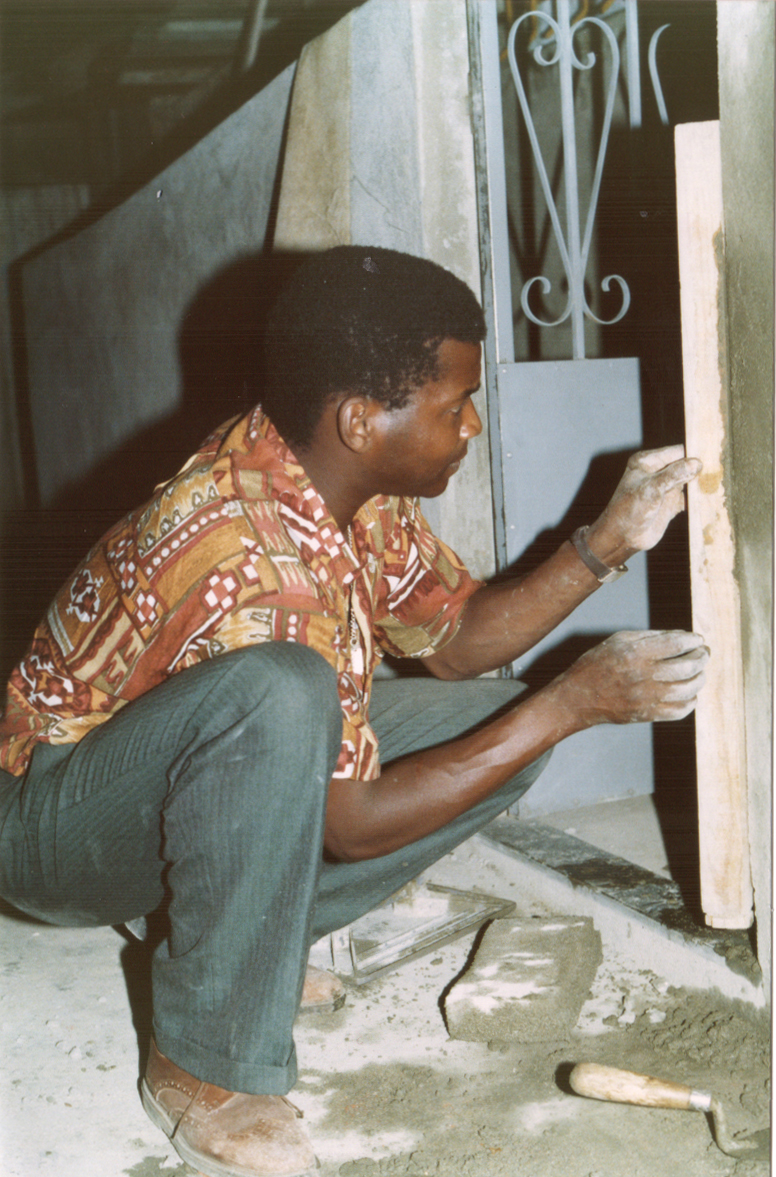

A resident building a dwelling, c. 1992. Photograph by Father Valentim Gonçalves.

Templates for building

A second glimpse concerns the way dwellings in informal settlements, despite their differences, often use similar building solutions. That was also the case in Quinta da Serra. Dwellings were copied and adapted from neighbouring houses, either because they were the only solutions available or because people were advised on arrival to do things in a certain way – in truth responding to shared material constraints, planning regulations or surveying practices. The way to go about foundations, walls, cess pits and roofing formed a minimum template for building, more or less followed according to individual cases, what we could term, following Gieryn (2002 as ‘repeated heterogeneity of design’. The indecision in a resident’s description between the way ‘her house was built’ and the ‘way houses were usually built’ is illustrative:

“The land was already levelled since it was previously used for gardening. So no steep or irregular inclinations. Then the foundations, the most important thing. Then you just erect walls. (…) For the foundations, you dig up to around 50 cm, then whoever is a bricklayer does them. Then some days to dry… and then you lay the walls. Bricks, cement, mortar… first you do the plasterworks on the inside, then on the outside. First comfort, then the outside. At least in our case it was like that. Then you pave the floor with tiles. That is hard work. (…) After the plasterworks you begin with adornments: my house has an arch at the entrance, the arch was done after the house. Then even out the street, put cement so you don’t have mud during wintertime or dust in the summer… do those things. …” (Interview, Aug 2008)

It reads as a ‘how to’ guide, from the house fundamentals to architectural signification. In this case, each task was compartmentalised, completed over time and in order. The different actions described took around one month for the house (with an accelerated construction rhythm) and the whole of the following year for the rest of the improvements (realised slowly). One of the fundamentals in this house was the cess pit:

“The cesspit was very deep. It was dug with a spade. I remember my father and his friends had to get up with the help of a ladder. It was at least 2 metres deep… And it was wide, almost as wide as a house. Then they divided it in half, each part for a different house. It had these little holes, like windows, directly to the earth. That was to absorb. Then they put a huge exhaust pipe. (…) They did it all with bricks, all around. Then they covered it with a concrete slab, and left a hole that is at the same time for exhaustion and in case it fills up.” (idem)

Overall, the majority of houses in Quinta da Serra had a properly functioning cesspit. Problems only occurred where a cesspit was too permeable to rainwater and flooded a neighbouring house during rain showers – the City Council provided de-sludging for these cases every few years. In 1999, a collective sewerage infrastructure was put in place and most residents connected their plumbing to it.

A shared technique: indoor bricklaying

Another feature common to many houses built from the early-1980s to the mid-1990s was a particular technique of bricklaying. This was seen when houses were upgraded from the wooden shack to the brick-wall house. It involved laying the bricks from inside the house, thus using the wooden walls as support and as a ‘bricklayers line’. There were two reasons for the technique. First, it was the most practical way to level the walls. However, if that was the primary reason, people would have simply done it on the outside. Second, and the crucial reason, bricks were laid from the inside with the intention of hiding construction from municipal surveyors, in case they would be looking for concrete or bricked fait accomplis in the middle of the wooden shacks (shacks were not a surveying priority at the time). That way, when the walls were finished, people simply tore down the wood structure and a brick-wall house would be standing in the same place.

Here, explicitly, the techniques of building were closely bound with the social, political and administrative context – a creative and intelligent way to circumvent the potential demolition of upgraded houses. However, this game between the state and illegal squatters was not really won by the latter because building a house this way ultimately hinders it becoming anything close to acceptable standards. The technique became part of the building mythology of places like Quinta da Serra, and many houses in the neighbourhood fit the description, especially upon close inspection of the joints between the walls and the floor, where no sign of strong foundations seem visible.

Precarious dwelling (without fundations) in Quinta da Serra, 2008.

So the dissemination of architectural vocabularies from formal or modernist models through the informal city, something that Lara (2010) shows in the Brazilian case – the appropriation by builders in favelas of Le Corbusier’s Domino model – was not possible in Quinta da Serra despite its population being very familiar with sophisticated concrete works. This was because surveying priorities ‘clamped down’ more forcefully on permanent structures such as the Domino than on shacks or their bricks-and-mortar upgraded versions, a practice derived from the tenets of the PER program to not allow ‘one more barraca’, so that the program would not perpetuate illegal construction. Architectural appropriation still existed, but was of a more traditional building technique, with load-bearing walls sustaining tile or fibre-cement roofs rather than the use of concrete pillars and non-load-bearing walls.

Communal Building

One final feature in the building of houses I wish to highlight here was the sharing of solutions and help from relatives, friends or work colleagues. These were the occasions where tacit knowledge was passed around, through doing:

“Like my mother says, he is such a ‘smooth talker’ he convinced all the Cape Verdeans and Guineans he knew [in the neighbourhood] to come help build the house. They used to work Saturdays back then, but on Sundays they came to build the house. The lady next door cooked for them. My mom was not with us at the time, it was just me and my sister. And he got help from work too. Sand, Flintstone, they offered some bricks… (…) They continued building like that, over some months. Back then people were more united… we had Cape Verdeans here, Guineans… Some of those who helped have died since…” (Interview, September 2008)

Help from friends is also part of the network of different elements that made that house a possibility. In STS language, this is called the summoning of allies, human or non-human, that make a specific network work (Bijker 1997, Latour 2005). The summoning of labour and knowledge (from friends), of social glue in the form of commensality (from the neighbour lady), of non-human actants like heavy equipment (the concrete mixer borrowed from Saturday afternoon to Sunday evening) or materials (flintstone and bricks), all came together to make this house possible. Through ‘smooth talk’ and a little help from his daughters:

“Our role, you know, was to carry water and bricks from the outside [of the alley] to the inside, as the house was circled by others and the concrete mixer and stuff had to be outside… it didn’t pass the narrow alley… And then of course, our role was also to keep them supplied with beers!” (idem)

The residents who built the house for the three nuns who moved to the neighbourhood in the early 1990s. Photograph by Irmãzinhas de Jesus Sisterhood.

Low-fi technologies for inhabitation

In addition to the ‘minimal template’ of building, residents used individual solutions to solve the problems that were not addressed collectively by the City Council. One of those solutions was individual water deposits, an effective low-cost technology used to overcome the nuisance of fetching water from the two communal wells. One of the advantages was that they provided hot water naturally given the sun warmed the deposits.

Before water provision: a resident stands proudly on top of his individual water deposit. Photograph by Father Valentim Gonçalves.

In the late 1990s, water from the wells was connected to some parts of the neighbourhood. In 1999, provision of an elementary sewage infrastructure was finally achieved after the visit of town councillor. She was disturbed by the unhygienic conditions – recalling “children playing by the open air sewage flows” (Interview, Jan 2008) [though she probably witnessed small flows from individual leakages] – and liaised with municipal engineers and warehouse keepers to quickly set up a basic network to which residents could subsequently connect. It was installed over a period of two months, laying glazed clay pipes that drained sewage into the main municipal sewage collectors.

“It’s not a standard infrastructure, in terms of following certain criteria and rules… It was done with minimum cost in terms of materials. Basically we ameliorated the undignified conditions in which those people lived… the open air sewage, the rats… it was a very serious situation. (…) It was an improvised, amateurish solution, done with scarce municipal resources, but that sought to solve the problem as quickly as possible.” (Interview, Jan 2008)

Even so, it was judged at first by officials from the municipality to not be worth the investment:

“I sought advice with the officials [técnicos], which of course are not insensitive to these matters. But it was said that in terms of cost assessment, it wasn’t worth it because the neighbourhood was to come down in the short to medium term. I thought ‘No!’, that any day was a good day to start solving the miserable conditions these people lived in. (…) You know how long an urban planning operation takes. Between conception and finishing many years can pass by. It was not foreseeable that that process would be concluded in one or two years.” (idem)

It was eventually given the go ahead, with labour provided by municipal workers. The infrastructure improved sanitary conditions, but the episode shows that the generalised assumption of clearance almost contributed to the lack of investment, and this a recurrent feature in informal settlements: as they are pending demolition any improvement is denied.

Electricity: a tragicomedy of illegal taps and power cuts

Finally, an informal technology used in the ‘urbanising’ process of the neighbourhood was the illegal tapping of electricity, which had been a general solution from the early days of the settlement. Puxadas, as taps are known, were connected to nearby posts, subdivided into groups of houses and then to individual dwellings. The population tapped electricity from legal customers, which led to complaints regarding loss of power to the public facility EDP – Electricidade de Portugal. As a result, a picket would be dispatched to cut power in parts or the entire neighbourhood. This was problematic in more ways than expected:

“Obviously these were illegal but that’s how it worked, that’s how people managed to survive. Even because we live in the age of electricity, right? Most of the food is sold assuming it will be kept refrigerated. People would buy food, store it in their freezers or refrigerator arcs… But every now and then power cuts happened. Food went bad, people were running around seeking for who might still have a running freezer so that they could keep their stuff. (…) So we began to mobilise ourselves. I joined a group of residents and we asked for legal electricity.” (Interview, Jan 2008)

That was in early 1991. For the following 7 years it worked this way:

“The picket man would come, accompanied by police forces, at the time it was the GNR [Guarda Nacional Repúblicana – Republican National Guard] from Sacavém, and they removed the taps. But they were cutting on one side and by their back people were already starting to stretch the wires from another point. It was like this, systematically.” (idem)

Power cuts, c. 1990. Photograph by Father Valentim Gonçalves.

Residents had to repeatedly buy street-purpose electric wire (stronger and more expensive than the domestic one) from the hardware store. Residents remembered well, not without a touch of resentment, “the amount of money he [the store owner] made out of our predicament” (Field notes, Jan. 2008). Legal provision was delayed because EDP needed property records, house registrations and other licences to open up an account, none of which existed for these illegal dwellings. It took seven years for the impediment to be cleared by authorisation from the City Council and a transitory solution arranged.

The slum built, managed and dismissed

In short, house construction in this and other settlements in Lisbon at the time began with an initial lack of money, later to be upgraded when more income was available. The techniques of construction responded in different times to housing policies and planning, in a complex circuit that also saw the latter be adjusted to the evolution of the dwellings in terms of materials or height. However, the expert definitions that were the basis for policy and for the work of the organisations that had the mission to manage these dwellings were de-synchronised from the actual dwellings, in that they assumed them to be still rudimentary. By accident or design, this situation resulted in a mindset within the technical-administrative milieu (Rabinow 1991) that these dwellings were invariably regarded as pending clearance and that populations would soon be rehoused in other areas. Therefore, improvement to existing houses was not a priority and infrastructure (water, sewage, electricity) was either provided with delays, was make-shift, or both.

Although the dwelling unit of the slum is materially constructed outside the established knowledges of the housing milieu, the ‘slum’ as a construct of the expert milieu only exists in an ‘after moment’, i.e. after the artefact has been built, upgraded, reconfigured and stabilised. Moreover, the construct in this case was deployed with the single purpose of demolishing the artefact, despite the existence of other paradigms such as upgrade or rehabilitation. In Quinta da Serra, the eventual option of an ‘assisted’ upgrade of the houses was not tried, not even as a provisional solution: everything waited for the ‘ultimate’ moment of clearance-rehousing, which became a story in itself, with the individual demolition of houses over an extended period of time opening up apocalyptic spaces in the middle of the neighbourhood and often showing for the first time the building techniques and makeshift technologies each house had relied on to exist.

References

Ascensão, E. (2011). The postcolonial slum: a geography of informal settlement in Quinta da Serra, Lisbon (1970s–2010). PhD dissertation, King’s College London.

Bijker, W. (1997). Of Bicycles, Bakelites, and Bulbs – Toward a theory of sociotechnical change, Cambridge and London: MIT Press

Gieryn, T. (2002). What buildings do. Theory and Society, 31, 35-74

Lara, F. L. (2010) The Form of the Informal: Investigating Brazilian Self-Built Housing Solutions, in Hernández, F., Kellett, P. and Allen, L., (eds.). Rethinking the Informal City: Critical Perspectives from Latin America. New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 23-38

Latour, B. (2005) Reassembling the Social – An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford University Press

Jacobs, J. M. (2006). A geography of big things. Cultural Geographies, 13: 1-27

Rabinow, P. (1989) French modern: norms and forms of the social environment. Cambridge and London: MIT Press.