Interventions II, Participatory Architecture - The SAAL

For two years in post-revolutionary Portugal, between 1974 and 1976, a housing scheme captured the imagination and shaped the practice of thousands of residents in shanty towns in Lisbon and in Porto’s inner city tenement slums called ilhas, as well as of the architects, urban planners, legal advisers and other professionals who were involved in the program. The SAAL – Serviço de Apoio Ambulatório Local (Mobile Service for Local Support) was a program of assisted self-building or assisted design which sought to respond to the severe housing shortages in the Lisbon and Porto metropolitan areas that Salazar and Caetano’s dictatorship had not been willing to address. During the two previous decades, in effect the urban poor were led to settle in scattered informal or illegal settlements in the periphery or in over-dense inner city slums (Nunes and Serra, 2004; Pinto, 2009; Salgueiro, 1977; Bandeirinha, 2007; Pinto, 2013; Queirós, 2013).

The program set up ‘brigades of technical assistance’ for each of the neighbourhoods or sites to be intervened on. It demanded that the construction of the new neighbourhoods was to be on the same sites of the existing ones (following the Portuguese derivative of the ‘right to the city’, the direito ao lugar (‘the right to the place’, which preempted displacement); that residents were to build their house with aid in materials and ‘technical advice’ from housing governmental agency Fundo de Fomento de Habitação (Housing Development Fund, from now on FFH) or from the freely-elected City Councils; and that rent payments to partly cover costs were to be calculated according to income. Finally, it stated that the brigades of technical assistance (legal, architecture project, financial accounting and construction) were not to substitute the populations: the government ‘lent a hand’ but those who were in need had to ‘take initiative’ (Ferreira, 1987, p. 83).

The brigades’ work

Respecting the principles of participatory social architecture – resident participation, user sovereignty and the self-help/self-built element taken from Turner and Fichter (1972) – interaction and exchange between experts’ and laypeople’s knowledge were thus intrinsic to the program’s methodology. This dialogue included exchanges about future house layouts (interior organization), morphology (density and street grid) and land tenure issues, all to be negotiated and designed in cooperation.

Women were strongly involved in the design process, “drawing the houses, telling [architects] where the bed would be, how to cross from one space to another” (Andrade, 2014).

What was intensely discussed, debated or negotiated varied according to the political and urban circumstances at each site. One of the most common dichotomies was between low- and medium-rise solutions, sometimes associated to the options to use variations of vernacular or late modernist housing languages. So for instance in Lagos’ Meia-Praia scheme, architect José Veloso proposed a design which was able to reflect as much as possible, in concrete, the positive elements of fishermen’s dwellings in canes or used industrial materials. At Bouça and especially at São Vitor, Siza designed a careful approximation to the ilhas’ morphology with a view to preserve the existing sociability, but of course with each house now having its own toilets instead of sharing one at the end of an inner patio (Grande, 2010, p. 21). In Lisbon, on the other hand, head architect Raúl Hestnes Ferreira and brigade architect Vicente Bravo Ferreira (part of a larger team) designed a late modernist medium-rise solution in Quinta da Calçada, with its back to the ring road Segunda Circular and a system of inner squares to address the issue of street life. The various experiments were in dialogue with the more progressive and participatory architecture of the time, which often played with architectural evolution and adaptation (e.g. Habraken’s [1972] Supports). Architect Francisco Silva Dias, for instance, designed the Alto do Moínho neighbourhood next to Bairro do Zambujal in the Oeiras municipality (today sitting next to an Ikea store) with a scheme that comprised self-built evolution, enabling residents to add rooms and other spaces over time (Bandeirinha, 2007, p. 385).

Architects and residents at a SAAL Meeting, Algarve, 1976. Photo by Alexandre Alves Costa

Participatory or social architecture became an integral part of the discipline from the late 1950s onwards, with several architect-theorists (Giancarlo de Carlo, Colin Ward, J.F.C. Turner, later N.J. Habraken) experimenting on different types of client-architect relationships and even on a different understanding of architecture itself, in the sense of an emphasis on the process rather than simply on its outcomes – the ‘housing as a verb’ trope Turner retrospectively introduced in 1972. User participation in the process of designing and building mass housing for the working classes was quickly transposed to interventions in informal settlements, namely Peruvian bairradas and Brazilian favelas. Among the latter was the influential intervention on the Favela Brás de Pina by architect Carlos Nelson dos Santos, which for the first time introduced the aim of ‘urbanising favelas’ (in the sense of infrastructure provision and plot division rather than clearance and displacement, as had at first been planned for the area) and assisted self-building with financial aid from public developer Codesco and National Housing Fund (BNH – Banco Nacional de Habitação). Residents were ‘assisted’ in house building only if they wished (the idea was to be as little normative as possible), and in fact house plans and layouts were first designed by households and only later reviewed by architects. The Brás de Pina experiment was an inspiration regarding many of its elements, but perhaps the most important is that it became a social elevator: by the mid-1970s the area was completely integrated in the adjoining lower-middle class area. The only weakness, though an important one and related to this, was that as the area became slightly more affluent many of the original recipients sold their houses and moved to other favelas. Unfortunately such outcome is still today repeated in many interventions in informal settlements: marked improvements to the social and built environment of a particular community do not solve structural poverty, and this is something which is worth keeping in mind. Notwithstanding, the Favela Brás do Pina experiment was an inspiration for many social architecture projects, especially in the Portuguese-speaking world. One was the SAAL housing program in Portuga. Below I look at it as an instance of urban technical democracy (Callon et al 2011) avant la lettre.

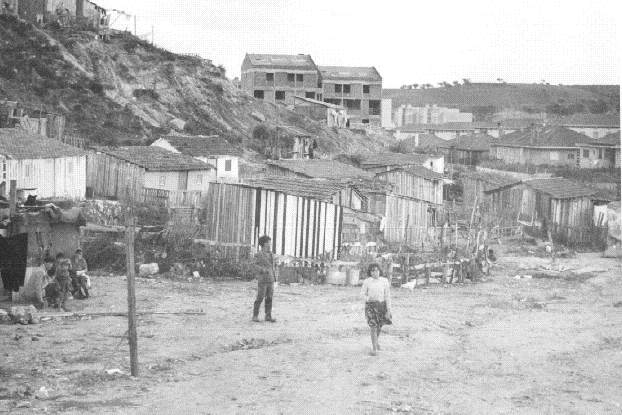

Azinhaga de Santa Luzia, Lisbon, 1969. Photo by Arnaldo Madureira, courtesy Arquivo Fotográfico Lisboa

The SAAL: technical brigades doing the revolution with residents

For two years in post-revolutionary Portugal, between 1974 and 1976, a housing scheme captured the imagination and shaped the practice of thousands of residents in shanty-towns in Lisbon and in Porto’s inner city tenement slums called ilhas, as well as of the architects, urban planners, legal advisers and other professionals who were involved in the program. The SAAL—Serviço de Apoio Ambulatório Local (Mobile Service for Local Support)—was a program of assisted self-building or assisted design, which sought to respond to the severe housing shortages in the Lisbon and Porto metropolitan areas that Salazar and Caetano’s dictatorship had not been willing to address. Although housing had been one of the key arenas in which the construction of modern citizenship in Portugal under the dictatorship was forged—namely through norms of social selectivity in the allocation criteria of the diminutive public housing stock (Nunes and Serra 2004; Pinto 2009)—in effect the urban poor were led to settle in scattered informal or illegal settlements in the periphery or in over-dense inner city slums (Salgueiro 1977; Bandeirinha 2007; Pinto 2013; Queirós 2013).

The SAAL set up ‘brigades of technical assistance’ for each of the neighbourhoods or sites to be intervened on. It demanded that the construction of the new neighbourhoods was to be on the same sites of the existing ones, following the Portuguese derivative of the ‘right to the city’, the direito ao lugar (‘the right to the place’, which preempted displacement); that residents were to build their house with aid in materials and ‘technical advice’ from housing governmental agency Fundo de Fomento de Habitação (Housing Development Fund, from now on FFH) or from the freely-elected City Councils; and that rent payments to partly cover costs were to be calculated according to income. Finally, it stated that the brigades of technical assistance (legal, architecture project, financial accounting and construction) were not to substitute the populations: the government ‘lent a hand’ but those who were in need had to ‘take initiative’ (Ferreira, 1987, p. 83).

This was a call to the cooperative grassroots movements (Bandeirinha 2007; Pinto 2013) and to facilitate it, the scheme was organised at each site with a Residents’ Committee responsible for relaying to the brigades exactly what was needed in terms of housing, land rights or social needs such as employment—for instance in areas with high unemployment, projects sought to sub-contract construction to unemployed residents organised in cooperatives (e.g. SAAL Curraleira Team 1984, 267).

The brigades’ work

Respecting the principles of participatory social architecture – resident participation, user sovereignty and the self-help/self-built (Turner and Fichter 1972) – interaction and exchange between experts’ and laypeople’s knowledge were thus intrinsic to the program’s methodology. This dialogue included exchanges about future house layouts (interior organization), morphology (density and street grid) and land tenure issues, all to be negotiated and designed in cooperation.

Women were strongly involved in the design process, “drawing the houses, telling [architects] where the bed would be, how to cross from one space to another” (Andrade, 2014). In a report, the SAAL team for the Curraleira neighbourhood explained how they had worked in this respect:

“Meetings were held with housewives in small groups of four where more detailed problems were solved, such as relations between kitchen, living room, and work space by changing partitions, doors, or equipment. Alternative finishes were also discussed and defined at these meetings. Field trips to other SAAL schemes in progress (…) were organized in this phase and to some housing component prefabrication plants as well.” (SAAL Curraleira Team 1984, 268)

What was intensely discussed, debated or negotiated varied according to the political and urban circumstances at each site. One of the most common dichotomies was between low- and medium-rise solutions, sometimes associated to the options to use variations of vernacular or modernist housing languages. So for instance in Lagos’ Meia-Praia scheme, architect José Veloso proposed a design which was able to reflect as much as possible, in concrete, the positive elements of fishermen’s dwellings in reed or old industrial materials. At Bouça and especially at São Vitor, Siza designed a careful approximation to the ilhas’ morphology with a view to preserve the existing sociability, but of course with each house now having its own toilets instead of sharing one at the end of an inner patio (Grande, 2010, p. 21).

Quinta da Calçada housing estate, Lisbon, 1977. Photo by Residents' Association Archive.

In Lisbon, on the other hand, head architect Raúl Hestnes Ferreira and brigade architect Vicente Bravo Ferreira (part of a larger team) designed a late modernist medium-rise solution in Quinta da Calçada, with its back to the ring road Segunda Circular and a system of inner squares to address the issue of street life. The various experiments were in dialogue with the more progressive and participatory architecture of the time, which often played with architectural evolution and adaptation (e.g. Habraken’s [1972] Supports). Architect Francisco Silva Dias, for instance, designed the Alto do Moínho neighbourhood next to Bairro do Zambujal in the Oeiras municipality (today sitting next to an Ikea store) with a scheme that comprised self-built evolution, enabling residents to add rooms and other spaces over time (Bandeirinha, 2007, p. 385). He recalls that in the following years, “residents would call me to ask for permission to build a new room in such or such way” (pers. comm., architect Filipa Serpa).

An adaptable dwelling in the SAAL typology, Telheiras, Lisbon, 2016.

A second recurrent issue debated by brigades’ members, residents and the FFH as competing technological frames (Aibar and Bijker 1997) was the option between self-building and professional contracting of construction. In some places such as the Relvinha neighbourhood in Coimbra’s periphery, residents wanted to build the houses themselves, “to feel they were ours” (Baía 2012, 125). In more politicized areas such as Lisbon’s industrial belt, where the Portuguese Communist Party or Trotskyist parties such as the PCTP-MRPP held considerable influence, residents complained about the “double exploitation” of having to work during the day in their usual jobs and then self-build their houses in the evenings, or well into the night (SAAL 1976, 119; Bandeirinha 2007, 141). Curiously, however, there was no overall winning frame in the sense that at each site the population, in dialogue with the FFH and the brigades, opted for what they decided was more convenient. This was an early example of something that could be taken as indecision or temporization, but that Callon et al. (2011, 191) appropriately call “measured action”.

Legally, too, important advances were made regarding land property arrangements. In Outurela, Oeiras after the public expropriation of land to construct the 18 de Maio neighbourhood, the sub-divided individual plots became collective cooperative property of the Residents’ Association, which today is still responsible for allocating houses (e.g. when an elder occupier dies) to its most-in-need members. Such implementation of a commons was aimed at avoiding future speculative activity with the land that had been expropriated with the sole purpose of guaranteeing housing for the poor.

These and other matters of concern all boiled down to one key issue, the speed of implementation. In fact, the different options could only be relevant elements for the new neighbourhoods if the latter were to exist at all. From the start, projects were envisaged to be built quickly, i.e. within an approximate timetable of 3 years, to avoid despair over ‘failed promises’ and ‘unfulfilled expectations’. One strategy to prevent discouragement was to start construction early on, with whatever means available, instead of waiting for FFH’s bureaucratic decisions to release the previously negotiated funding (Baía 2012, 126). And all these things—dialogues between slum dwellers and architects, options regarding housing density or architectural style, construction modalities, expropriation and collective property, urgency—were set amongst the revolutionary atmosphere, in which the citizenship status of slum dwellers (hitherto considered neglectable) and the way the city was produced (a capitalist-corporate mode of production) were to be radically altered.

The SAAL meeting at Palácio de Cristal, Porto, 5 April 1975. Top, women vote. Bottom, the representatives of each local association. Photos by Alexandre Alves da Costa.

What did social architecture during the revolution achieve?

If we analyze the SAAL with Callon et al.’s (2011, 160) parameters for dialogical procedures, we can argue the program’s methodologies and expert-laypeople interactions involved a high degree of intensity (translation for the involvement of laypeople in the exploration of possible worlds and the concern for the composition of a collective); as well as of diversity (translation for the diversity, independence and representativity of laypeople in the established action groups); but that, regarding its quality (related to the seriousness and continuity of the voice of laypeople), it oscillated between an undeniable ‘seriousness of voice’ and an unfortunately curtailed ‘continuity of voice’ owing to the program’s dismantlement.[1]

With hindsight, Álvaro Siza proposed, with semiotic precision, that this process was intense but that it still involved a form of mediation: “Commitment to residents did not mean to directly assume all their aspirations, but rather to be permanently aware of being in the process of representing their interests through a particular form of representation, which in this case was architecture” (Siza in Bandeirinha 2007, 254). In other words, although architecture as a scientific discipline did not supersede laypeople’s aspirations or worldviews, it still formatted them. Dialogue was instituted but circumscribed within discrete disciplinary boundaries.

Towards a more just urban cosmopolitics

The SAAL is especially illustrative of the tension between technical democracy’s tenets and working frameworks (dialogical or delegative), on the one hand, and the workings of urban capital formations, on the other. In the 1970s it constituted a progressive housing program, which instituted participatory democracy and a collaborative framework between the state, experts and target populations to solve an urgent problem, but it went against the capitalist status quo (particularly regarding urban land property) and was halted.

In light of this, Callon et al.’s (2011) hopeful tone regarding the potential of technical democracy needs to be weighed against actually existing outcomes of proto- or full technical democracy initiatives—especially in those arenas where the power imbalances between experts and laypeople are extreme (and intervention in slums is one such case). In the urban arena the potential of technical democracy tends to interrelate with, or come up against, other elements, including urban capital’s particular type of agency. Mechanisms of urban capital accumulation, although not necessarily a pervasive hidden force which supersedes all things, nonetheless tend to minutely disrupt, sabotage, suspend or cancel actually existing initiatives of cogent expert-laypeople interaction and general social emancipation.

In the process, real estate funds, developers and so on can, and often do, tweak, subvert or bypass regulatory frameworks to their advantage. A by-product of this situation is that the collaborative efforts and multiple agencies assembled around the potential of technical democracy can be brushed aside or crushed. This is not to suggest that the potentials of technical democracy are irrelevant (quite the contrary), only that they come up against adversarial elements and need to be prepared to face them.

Technical democracy is only such a thing (and not simply technocracy) if laypeople’s wishes are integrated in procedures and operations. As Callon et al. (2011, 248) identify: “What is essential for ordinary citizens and laypersons in dialogic democracy is not participating, but weighing up and contributing.” This is easier stated than found, but it is a point from which to depart if we are to recognize that the tenets of dialogic technical democracy are much needed in any future arrangements for a truly just urban cosmopolitics (Farías and Blok 2016).

References

Aibar, E. and Bijker, W. (1997) ‘Constructing a City: The Cerdá Plan for the Extension of Barcelona’, Science, Technology, & Human Values 22(1), pp. 3-30.

Andrade, S. (2014) ‘Melhorar a vida e a cidade, quarto a quarto’, in Público 31/10/2014.

Baía, J. (2012) SAAL e Autoconstrução em Coimbra: memórias dos moradores do Bairro da Relvinha 1954-1976. Castro Verde: 100 Luz.

Bandeirinha, J.A. (2007) O Processo SAAL e a Arquitectura no 25 de Abril de 1974. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade.

Callon, M., Lascoumes, P. and Barthe, Y. (2009) Acting in an uncertain world: an essay on technical democracy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Duarte, M. (2014) ‘As discussões eram de uma sinceridade absoluta, muitas vezes conflituosa’, in Público 10/11/2014.

Farias, I. and Blok, A. (eds.). (2016). Urban cosmopolitics: agencements, assemblies, atmospheres. London: Routledge.

Ferreira, A.F. (1987) Por uma nova política de habitação. Porto: Afrontamento.

Grande, N. (2010) ‘Revolución y Regeneración Urbana. El Bairro da Bouça de Álvaro Siza: entre el clavel y el bolígrafo’, La Ciudad Viva 3, pp. 20-26.

Habraken, N. J. (1972) Supports: an alternative to mass housing. London: Architectural Press.

Hatch, C. (ed.) (1984) The scope of social architecture. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Nunes, J.A. and Serra, N. (2004) ‘Decent housing for the people: urban movements and emancipation in Portugal’, South European Society & Politics 9(2), pp. 46-76.

Pinto, P.R. (2009) ‘Housing and citizenship: building social rights in twentieth century Portugal’, Contemporary European History 18(2), pp. 199-215.

Pinto, P.R. (2013) Lisbon Rising: Urban Social Movements in the Portuguese Revolution, 1974–1975. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Queirós, J. (2013). Precariedade habitacional, vida quotidiana e relação com o Estado no centro histórico do Porto na transição da ditadura para a democracia. Análise Social 206, pp. 102-133.

SAAL (1976) Livro Branco do SAAL – Volume 1. Lisboa: Conselho Nacional do SAAL.

SAAL Curraleira Team (1984) ‘Designing Curraleira’, in C.R. Hatch (ed.) The scope of social architecture, pp. 265-269. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Salgueiro, T.B. (1977) ‘Bairros clandestinos na periferia de Lisboa’, Finisterra: Revista Portuguesa de Geografia 12(23), pp. 28-55.

Turner, J.F.C. and Fichter, R. (eds.) (1972) Freedom to Build: Dweller control of the housing process. New York: Macmillan.

[1] By 1976, the program’s exemplification of direct democracy, which had served to legitimize the new democratic state, was considered by many a threat for the country, now exiting its revolutionary period and entering a period of normalization, towards a market society. Any experiences that could be seen as alternatives to ‘normal’, parliamentary and representative democracy were swiftly eliminated. Bandeirinha (2007, 175-218) describes this winding down in great detail: the responsibility of implementation was passed from the FFH to the different municipalities where sites were located; the latter were much more permeable to private interests from corporate land owners or to top-down ideological diktats regarding the irrevocability of private property than the circumscribed and coherent SAAL team at FFH (the Porto offices of which were bombed by right-wing militants on 14 January 1976), which was highly flexible regarding the different solutions for each site, provided residents’ wishes were fully integrated into them. The SAAL’s dismantlement can be summarized by the fact that only 7,000 of the planned 40,000 dwellings were ever completed.